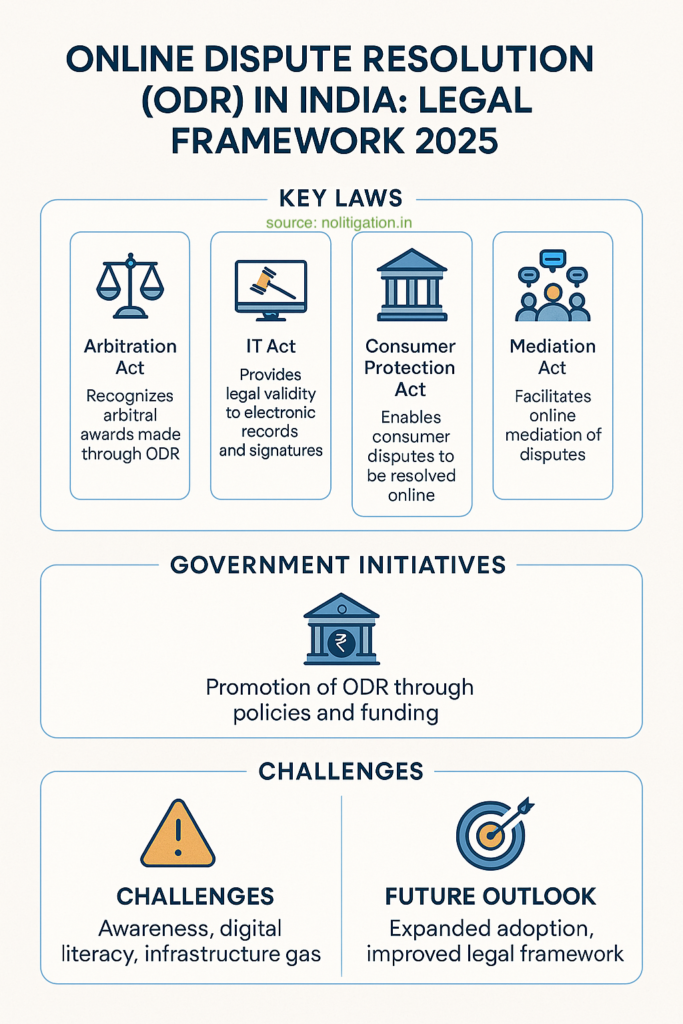

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving legal framework supporting ODR in India as of 2025. It explores the key statutes and recent legislative reforms that underpin ODR, highlights government initiatives fostering its growth, discusses challenges within the legal ecosystem, and examines future legal frameworks and reforms necessary for mainstreaming ODR in India’s justice delivery system.

Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) has emerged as a transformative mechanism addressing the longstanding issues of access, cost, and delay in India’s overburdened judicial landscape. By leveraging digital technologies, ODR facilitates dispute resolution anytime and anywhere, presenting a promising complement or alternative to conventional courts and tribunals. However, the widespread adoption of ODR critically depends on the robustness and clarity of the underlying legal framework which supports its legitimacy, enforceability, and regulatory oversight.

ODR: Necessity and Potential in India’s Justice Ecosystem

India’s judicial system suffers from an enormous backlog exceeding 5 crore (50 million) pending cases as of 2025 (link), resulting in years-long delays for most litigants. Geographic, economic, and procedural barriers exacerbate the situation for marginalized sections of society. Against this backdrop, ODR offers a technology-enabled solution that can reduce court congestion, lower litigation costs, and ensure quicker, accessible resolution of disputes outside traditional courtroom settings.

ODR uses online communication tools such as videoconferencing, secure portals, and automated negotiation algorithms, to enable negotiation, mediation, and arbitration processes remotely. It is particularly useful for resolving civil, commercial, consumer, and small-value claims efficiently while maintaining procedural fairness and confidentiality. The concept aligns with constitutional goals under Article 39A, promoting affordable and equitable access to justice for all.

Foundational Statutes Supporting ODR in India

Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

The Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 remains the primary legal framework governing arbitration in India, including ODR-based arbitration. While not drafted explicitly for online disputes, its provisions have been interpreted by courts to accommodate virtual hearings, electronic communication, and digital evidence. Notable amendments introduced in 2019 and the new Arbitration Act of 2025 emphasize swift adjudication—mandating arbitral awards within 12 months—and promote institutional arbitration, thus encouraging the use of technology-enabled platforms for dispute resolution.

Information Technology Act, 2000

The IT Act provides the crucial legal infrastructure for ODR by granting electronic records and digital signatures legal recognition equivalent to paper documents and handwritten signatures. Sections 4 and 5 of the Act validate electronic contracts and signatures, enabling parties to conclusively agree on dispute resolution terms online. Section 10A fortifies the enforceability of electronic agreements to arbitrate or mediate, while Sections 65 and 66 address cyber crimes like hacking and fraud ensuring security in ODR transactions. Overall, the IT Act 2000 provides a strong legal framework for ODR.

Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (Amended)

The Indian Evidence Act’s amendments, especially Section 65B, allow the admissibility of electronic evidence in legal proceedings, reinforcing ODR outcomes with strong probative value in courts. This provision is essential for recognizing documents, communications, and contracts processed or generated through ODR platforms as valid evidence.

Code of Civil Procedure, 1908

The procedural code permits flexible methods for pre-litigation resolution and supports digital procedural modalities such as e-filing, virtual hearings, and electronic document exchange, paving the way for integrating ODR mechanisms within court systems. Recent practices of courts holding virtual hearings during the COVID-19 pandemic have set important precedents for digital dispute resolution acceptance.

Consumer Protection Act, 2019

The Consumer Protection Act created mandatory mechanisms for consumer grievance redressal through mediation and ODR, particularly mandating e-commerce and digital service providers to offer online dispute resolution for consumer complaints. Consumer mediation cells established at various jurisdictional levels emphasize quick, informal resolution reflecting the adaptability of ODR within consumer law.

Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987

While traditionally focused on legal aid and Lok Adalats, the Act now increasingly supports digital mediation and Lok Adalats through e-Lok Adalats initiatives, integrating ODR into alternative dispute resolution (ADR) frameworks and expanding access for economically weaker sections.

Mediation Act, 2023

A landmark reform recognizing online-mediated settlements, the Mediation Act requires that mediated agreements be in writing, signed electronically, and registered with authorities. It mandates confidentiality and enforces strict ethical standards for mediators, thereby formally acknowledging ODR-enabled mediation as a legitimate dispute resolution process within Indian law.

Government Initiatives and Policy Frameworks Promoting ODR

India’s central and state governments have actively championed the digital transformation of dispute resolution via:

NITI Aayog’s ODR Policy Plan (2023): This visionary blueprint proposes a three-tiered ecosystem employing AI-driven negotiation tools for small-value disputes, online mediation for mid-level disputes, and virtual arbitration for commercial conflicts. It recommends strengthening digital literacy, infrastructure, and training for legal professionals to enhance ODR adoption.

• e-Lok Adalats: Central and various state authorities have institutionalized these virtual Lok Adalats to resolve disputes swiftly through online platforms, reducing pendency significantly.

• MSME SAMADHAAN: A government-endorsed portal facilitating online dispute resolution for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), ensuring faster resolution without needing physical court appearances.

• Judiciary’s Tech Adoption: The Supreme Court and High Courts have encouraged virtual hearings and upheld the validity of electronic evidence and agreements, signaling judiciary support towards ODR mechanisms.

Legal Recognition and Enforcement of ODR Outcomes

ODR’s legitimacy in India largely hinges on the enforceability of its resolutions. Awards and settlements achieved through ODR processes are legally binding under extant arbitration and mediation laws when parties voluntarily agree to these mechanisms. Courts have progressively upheld such outcomes, provided they comply with procedural fairness, consent, and authenticity standards.

Judicial pronouncements have confirmed that orders and documents exchanged electronically under ODR platforms hold the same weight as physical documents. The IT Act and Evidence Act provisions ensure that electronically signed settlements and digital evidence in ODR cases are admissible and enforceable in court proceedings.

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations for ODR Providers

Despite existing legal backing, a dedicated regulatory framework specifically for private ODR platforms remains absent. The Arbitration Act and other statutes do not directly regulate ODR providers’ operational standards, leading to concerns about:

• Platform transparency and impartiality

• Data privacy and cybersecurity safeguards

• Accreditation and accountability of mediators/arbitrators

• Consumer protection and grievance redressal mechanisms

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 offers comprehensive guidelines on safeguarding personal data and privacy in digital interactions, which is critical for user trust in ODR platforms. However, to address the unique needs of ODR, there is a pressing requirement for sector-specific regulations that establish clear standards for licensing, operational conduct, and data governance of ODR providers. These could include mandatory certification of platforms for security compliance, transparency requirements about data use, and defined protocols for handling sensitive dispute-related information.

Drawing from successful models in other sectors, self-regulatory organizations (SROs) are being proposed to oversee ethical standards, mediate consumer grievances against platforms, and conduct regular audits to ensure accountability. The establishment of such regulatory and oversight mechanisms will help bridge current gaps, foster greater stakeholder confidence, and create a structured environment conducive to the sustainable growth and mainstream adoption of ODR in India.

Furthermore, ongoing public consultations and government initiatives signal momentum toward formalizing these frameworks, with integration of technological advances like AI and blockchain anticipated to be complemented by robust legal safeguards in the near future.

Challenges Within the Legal Framework and ODR Ecosystem

Numerous challenges temper the full realization of ODR’s potential in India:

• Legal Ambiguities: Most ADR legislative frameworks do not explicitly envisage online modalities, causing uncertainties around the enforceability of purely online private arbitration awards without judicial supervision. To address legal uncertainties, NITI Aayog’s 2023 ODR Policy Plan advocates for explicit legislative amendments in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act and Code of Civil Procedure to formally recognize online dispute resolution processes. These reforms aim to clarify enforceability standards of purely online arbitration awards and integrate ODR as a mainstream judicial alternative

• Digital Divide: Limited internet access, digital literacy gaps, and infrastructure deficiencies, especially in rural and remote regions, restrict equitable participation in ODR. The government is investing in expanding digital infrastructure and promoting digital literacy initiatives targeting rural and underserved communities, ensuring wider equitable access to ODR platforms. Public-private partnerships and local language support tools are also being developed to bridge accessibility gaps for marginalized populations.

• Resistance from Legal Professionals: Traditional lawyers and judiciary members sometimes resist digital transformation due to unfamiliarity or concerns over procedural rigor. Training programs and certification courses for lawyers and judges are being rolled out to familiarize legal professionals with ODR technologies and processes, reducing resistance and increasing acceptance. The judiciary’s own increasing use of virtual hearings serves as an important example encouraging traditional practitioners to embrace digital dispute resolution

• Lack of Specific Regulations: The absence of dedicated laws defining roles, responsibilities, and standards for ODR providers causes operational risks and limits trust. Policy proposals suggest instituting dedicated self-regulatory bodies and clear operational guidelines for ODR providers to ensure transparency, accountability, and data privacy. Emerging regulatory frameworks are expected to include standards for mediator accreditation, platform governance, and consumer protection in ODR transactions.

Future Directions for Legal Reforms

To institutionalize ODR as a mainstream justice delivery mechanism, India needs to:

• Introduce explicit statutory recognition of ODR within the Code of Civil Procedure and Arbitration Act, clarifying enforceability and procedural safeguards.

• Develop comprehensive regulatory frameworks establishing licensing, accreditation, and ethical codes for ODR platforms and neutrals.

• Enhance interoperability and data sharing standards while strengthening cybersecurity and consumer protection laws applicable to ODR.

• Promote public awareness and capacity-building programs to foster trust and legal community acceptance.

Several stakeholder consultations, including those by NITI Aayog and legal think tanks, advocate a light-touch, enabling IP-technology law approach that balances innovation with accountability.

Conclusion

The legal framework supporting Online Dispute Resolution in India as of 2025 reflects a dynamic and evolving intersection of traditional laws, digital statutes, and progressive reforms. Well-established statutes such as the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, Information Technology Act, Consumer Protection Act, and the Mediation Act collectively endorse the procedural validity, enforceability, and accessibility of ODR outcomes. Government initiatives and judiciary endorsement have further accelerated its adoption.

However, addressing existing regulatory gaps, digital infrastructure challenges, and legal uncertainties will be pivotal for ODR to achieve its full promise. Continued legislative refinement, regulatory oversight, and technology-enabled capacity-building will ensure that ODR becomes a credible, efficient, and inclusive alternative to conventional dispute resolution, ultimately expanding access to justice for millions across India.